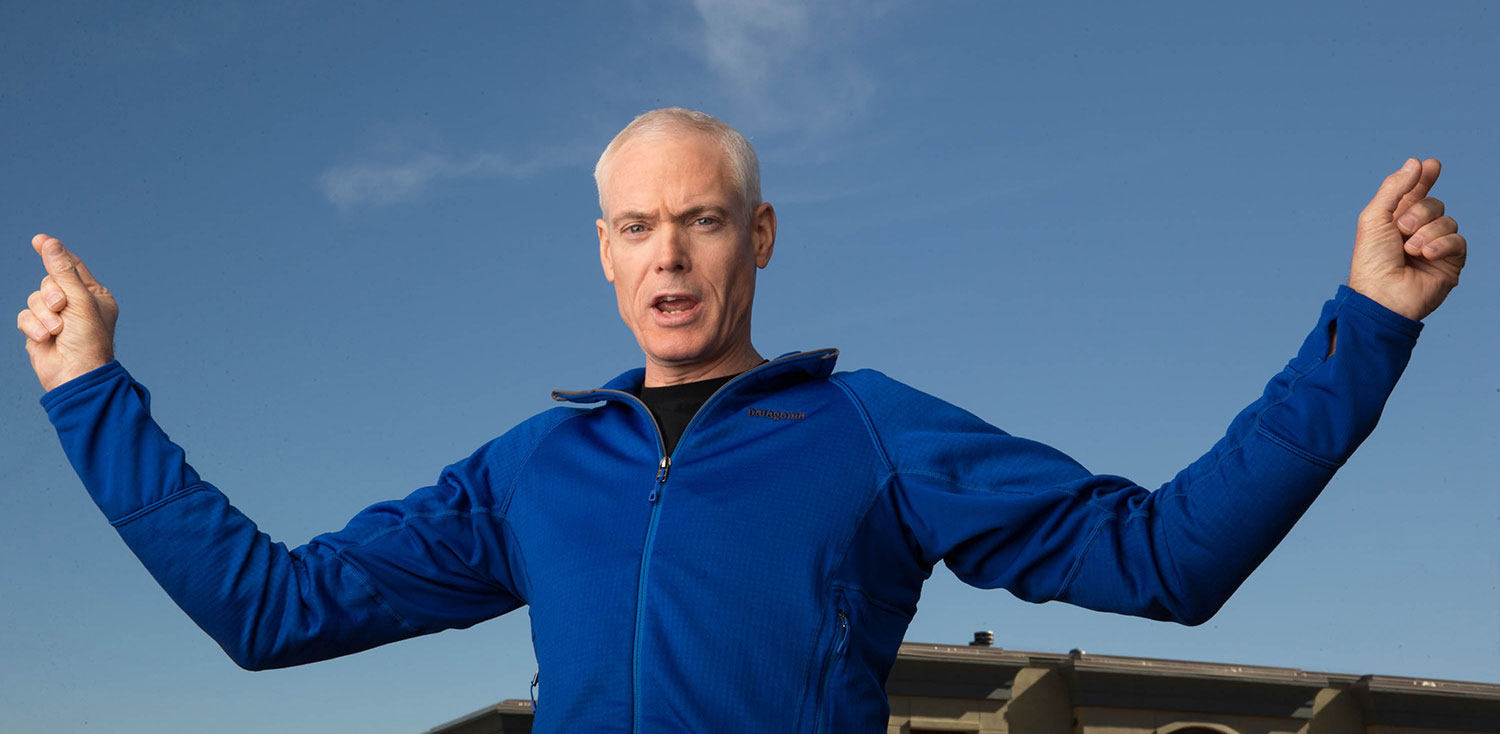

Investment banker, philanthropist, art collector and self-made millionaire Simon Mordant AM discusses his views on leadership, management and the valuable role art plays in the mix. Story by Anthony O’Brien and photo by Daniel Boud.

SIMON MORDANT needs little by way of introduction. Renowned as one of Australia’s most successful investment bankers, he has a powerful reputation in business advisory, having co-founded Caliburn Partnership – the firm that successfully navigated some of Australia’s biggest mergers including Westpac’s $18 billion move on St George Bank in 2008, a merger that many thought would never pass muster with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

In 2010, Mordant and his partners sold Caliburn to Greenhill & Co in a deal valued at about $200 million. But just five years later, hungry to repeat his success, he teamed up with former business partners Ron Malek and Jamie Garis to launch Luminis Partners.

Despite his undoubted mastery of the deal, Mordant is perhaps best known for his passion for the creative arts. A visit to Luminis is a visual feast, providing an opportunity to view the impressive collection of artworks Mordant has acquired over the past four decades.

Indeed, it was their philanthropic support of the arts community that thrust Mordant and his wife Catriona into the public eye. In 2010, the couple donated an incredibly generous $15 million to Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), to help to fund a new wing. As a leader of the funding campaign Mordant couldn’t make the donation anonymously, yet he admits

to being wary of the scrutiny that would inevitably follow.

Mordant recalls, “We were incredibly nervous about what the community would say. I was nervous about what my team would think. I was nervous about what my clients would think.”

The donation was critical to garnering government support and getting the project over the line. “It was a game of poker,” says Mordant. “We were both so invested in that project that we thought we’d roll the dice.”

Mordant had the winning hand. His donation sparked a $26 million contribution from the federal and NSW governments, and the new wing – the aptly named Mordant Wing — was completed in 2012, extending the size of the MCA by 50 per cent and leading to over a million visitors each year. In that same year, Mordant was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his service to the arts and cultural community.

It’s a far cry from the young man who arrived in Australia “with nothing”. Nothing material perhaps, but Mordant had plenty to offer the business community. He started his career in accounting – and to a large extent still works in a numbers game. However, he doesn’t see a head for figures as critical to success. Indeed, Mordant believes good leadership comes down to three key attributes.

First and foremost is the ability to distil information quickly. “There is so much information thrown at you,” he says. “Understanding what that information is, what is important and being able to interpret it is key.”

Mordant’s most critical skill is his ability to listen. “Being able to listen is very important,” he explains. “I’ve often thought that an advisor is like a corporate psychiatrist. We can’t claim to be experts in our clients’ industries, and when a client comes to us to help them through a problem, they invariably already have the answer. They may not have confidence that they have the answer, or evidence that it’s the solution they’re looking for, but they often have an intuitive sense of what will work because it’s their business.

“Where the advisor comes in is to listen, probe intelligently, ask the right questions to draw out the client in explaining what the issue is, and then brainstorm. You can’t do that if you talk all the time.”

For Mordant, the third valuable attribute is having the confidence to make decisions. He notes, “I’ve seen people who are very strong at the first and second qualities but fall at the third. And at the end of the day you’ve got to be able to make a decision. Not all your decisions are going to be perfect in hindsight, but a leader has to be able to make a decision.”

Describing his leadership style, Mordant says, “I’m a very caring person; I’ve learnt to be empathetic. I wasn’t when I first started out, but I’ve learnt that that’s very important.” He may fine-tune his style according to the situation but he believes the same skills apply.

“When I run the business I obviously have to make decisions. When I sit on the board of a not-for-profit, I’m there to challenge and support the chief executive.

So my style is a little bit different but the skills I employ are very similar. I listen, I draw out, I probe.”

NOURISHING THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE BRAIN

For Mordant, engagement with the creative arts goes beyond a personal interest: it plays a noteworthy role in his business success. “Creativity and leadership are very intertwined,” he says. “In a business like ours, every problem is new and different and can’t be cookie cut. We need to provide bespoke solutions, and creativity is vital.”

This need for creativity goes a long way to explaining the pageant of artworks on display at Luminis’s offices. “I want the team to be challenged by works of art, and I want our clients to be challenged.”

Clearly, Mordant is delighted when the artworks have their desired effect. He recalls how a client waiting to speak with Mordant went missing. “I came in to welcome him and he wasn’t in the meeting room,” explains Mordant. “The door was open, and I couldn’t work out whether he’d gone to the bathroom or whatever. In fact, he was wandering around the office, just immersed in the paintings. It was fantastic.”

The ability for art and business to feed both sides of the brain matters to Mordant. “Emotional intelligence and empathy are deeply connected with leadership.” He adds, “I’ve seen incredibly smart leaders who have no emotional intelligence. And invariably those businesses are impacted by that.”

Mordant believes “all business leaders should engage with something creative outside of their business.” He says, “At the MCA, we now run a corporate program, and we’ve had a number of leadership teams hold part of their planning days in one of the creative spaces. It just takes you into a different place.”

RESILIENCE IS VITAL

Mordant’s diverse interests, and his unwavering commitment to each of them, could exact a high personal toll. It’s an area where he says resilience plays a valuable role. “The demands on leaders today are 24/7,” notes Mordant. “The way technology works, you’re accessible the whole time and that does require a high degree of resilience.”

His personal resilience is also vital to the success of his team. “In our business, transactions have a very long lead time,” explains Mordant. “If you get a project completed in nine months, that’s fast. Projects can come on and off the boil over many years, and at the end of the day, sometimes they’re not successful, they just peter out.”

“The ability to hang in there and motivate your team, who are doing the work through the ups and downs of a transaction, is really key.”

Resilience has served Mordant well in the arts community also. In late 2017 he pulled out of funding Australia’s next exhibition at the Venice Biennale when the Australia Council failed to consult major donors about changes to the arts commissioning model.

It was a very public stoush, but Mordant felt compelled to speak out.

“When you are used to being forthright in the advice you give, you need to have the same values in your personal life,” he says. “If I didn’t say something publicly, everyone would assume I was comfortable with the arrangements. I felt I had a duty to the people who had partnered with us to make my views known.”

COMMITTED TO PERSONAL WELLBEING

Mordant may have just left the board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation but his schedule hasn’t eased. He’s chair of the MCA and on the board of numerous not-for-profit organisations including the Garvan Research Foundation, MoMA PS1 in New York and the American Academy in Rome, to name a few. He also chairs the Barangaroo Lend Lease Public Art Program, with a $40 million budget to put public art at Barangaroo.

Such commitments can often involve a smorgasbord of social engagement. Down the years, that caught up with Mordant.

“Sitting down at 9pm at a function, if there were bread rolls there, I’d eat them,” he recalls. “If there was bad wine there, I’d drink it.”

With his weight topping 120 kilograms, Mordant admits, “I couldn’t buy any clothes from a shop; everything had to be made.”

The lightbulb moment came when he left Caliburn, and headed to Italy for a year. “When I was in Sydney, I was out every night. I couldn’t control my environment, whereas sitting on the top of a mountain in Italy, I was in a completely controlled environment and I thought I’d try and lose 20 kilos.”

The basis of Mordant’s weight loss success was simple.

He explains, “I just reprogrammed my brain. I cut out carbs, bread, rice, sugar, potatoes and pasta. It didn’t mean I didn’t put bad things in my mouth occasionally, but it became a conscious decision. I cut out wine too, and as a partner in a winery that was pretty challenging.”

Mordant didn’t just lose 20 kilos: he lost 60 – half his original body weight. And his best tip for managing well-being as a business professional is: “Think about what you put in your mouth. It’s a pretty simple thing to do, but for 55 years of my life, I never thought about it.”

Leadership in 60 seconds

EARLY IN YOUR CAREER WHAT IS THE BEST PIECE OF LEADERSHIP ADVICE YOU WERE GIVEN?

Listen, don’t talk.

WHICH LEADER HAVE YOU LEARNT FROM MOST DURING YOUR CAREER?

Let me answer that in two ways. The leader I learnt the most from during my career would have to be Giles Kryger, who was the Managing Partner of Ord Minnett, when I was there in the early 1980s. The business leader I have admired most during my career is Alan Joyce, CEO of Qantas.

NAME THREE LEADERS IN THE ARTS AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES WHO YOU ADMIRE?

The first one has to be Liz Ann Macgregor, Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. The second would be Justin Milne, Chair of the ABC. Third would be Glyn Davis, outgoing Vice Chancellor of the University of Melbourne.

WHICH LEADERSHIP BOOK DO YOU MOST RECOMMEND?

That’s a no-brainer for me, Good to Great by Jim Collins. The way Collins contrasted the best performing companies in their sectors with the worst performing companies, to draw out a set of characteristics around leadership in the successful companies versus leadership in the unsuccessful companies was fascinating. I’ve applied some of those learnings to Australian companies, and it’s very illuminating.

NAME THREE QUALITIES THAT A LEADER CAN’T SUCCEED WITHOUT?

Empathy. Listening skills. Decisiveness.

COMPLETE THE SENTENCE. LEADERSHIP MATTERS BECAUSE…

Everything is changing rapidly and you must be able to lead your organisation through change, in order to meet its ambitions.