Dr Daniel Jolley IMLa is no stranger to the fine art of decision making. As a consultant anaesthetist, he is called upon to demonstrate leadership and make life-saving decisions in an environment where split second timing can be critical.

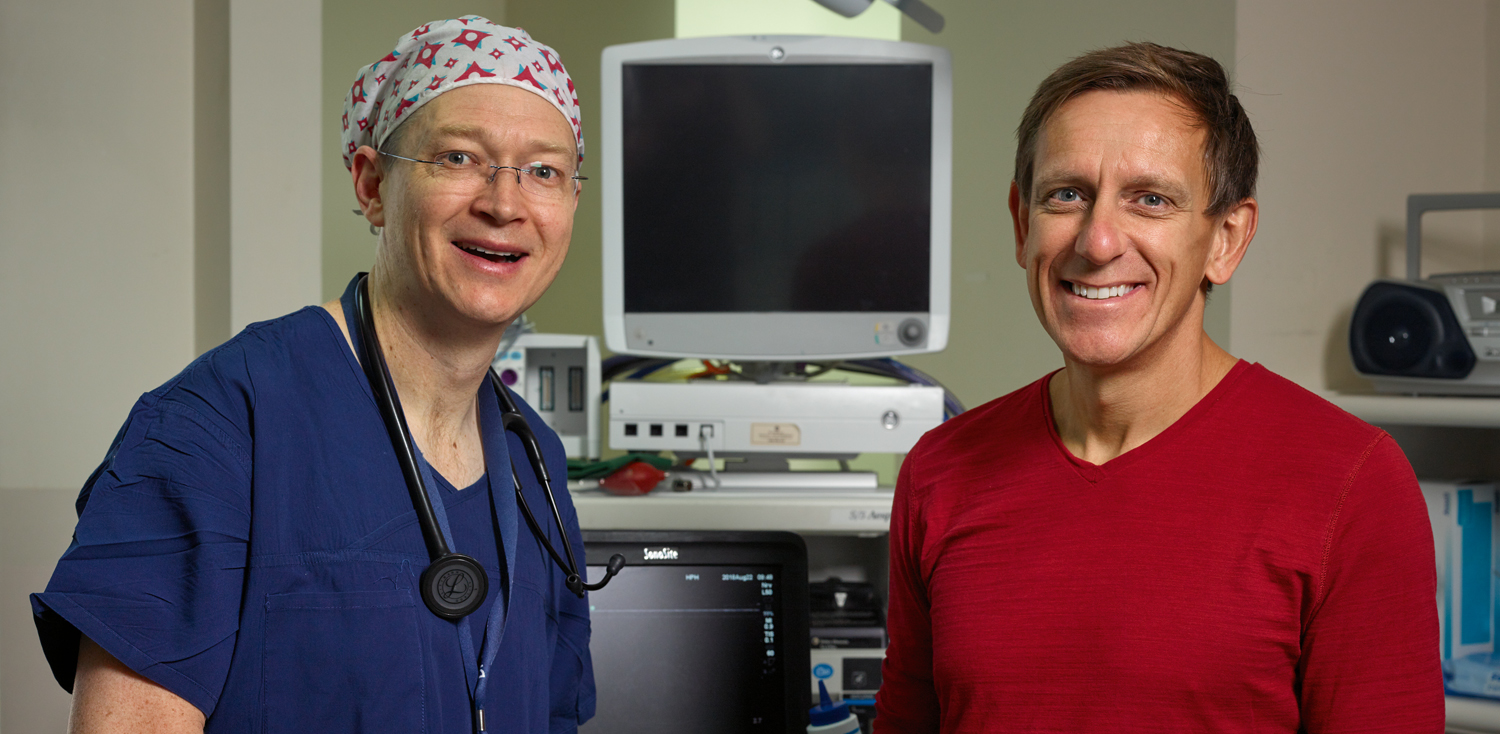

Story by Nicola Field // Photography Peter Whyte

Dynamic decision making is the name of the game in an operating theatre. As Dr Daniel Jolley explains, “You try to be proactive rather than reactive.” Like all good skills, this comes with training. Anaesthesia requires a minimum five-year training period, often spent working alongside senior anaesthetists. Nonetheless, Dr Jolley observes that these days, the safety factor of surgery often hinges more on the decisions made by an anaesthetist rather than drugs, technology,

or equipment.

To learn more about how Dr Jolley rises to the leadership challenge – and why as a medico, he opted to undertake management and leadership training – IML CEO David Pich FIML met him in Hobart.

David Pich: In leadership we tend to think somebody is in charge, and others follow instructions. But it doesn’t sound like that’s the case in an operating theatre.

Dr Jolley: Australia is quite unique in that the position of the surgeon and the anaesthetist are on more of an equal footing. Coupled with the Australian willingness to challenge authority, members of the theatre team are less likely to be totally subservient to the perceived leader in the room. It’s interesting from a safety point of view – and this is something that’s been heavily studied inside the airline industry. There is a reasonably strong theory, for example, that Qantas continues to be the safest airline in the world both because of the exceptional training the airline invests in its pilots, but also because of the cultural tendency, in Australia, to challenge authority.

It’s the same in a theatre. It’s not uncommon for my aesthetic nurses to very carefully say, “Are you sure you want to do that?” So there’s a shared leadership role in the theatre environment.

DP: Before you walk into the operating theatre, is there a briefing session?

DJ: There’s been a big push over the past five years for a team meeting at the start. We have a brief discussion of every patient on the operating list so that the surgeon, anaesthetist and nursing staff can raise any concerns about potential problems and ensure everybody’s on the same page. You’re basically preparing for the unexpected, so that when the unexpected happens, it can be handled in a safe and effective way.

DP: That’s interesting because a major focus for IML, at the moment, is the concept of intentional leadership. In order to end what we call ‘the chaos of accidental management’, you have to intend to lead. Are you saying intentional leadership is alive and well in our hospitals, and it cuts down the opportunity for accidents to happen?

DJ: The surgeon is largely the default leader. But that leadership role can change very quickly in emergency situations, and when that happens, it occurs smoothly and without any real tension.

Where there’s say, a cardiac arrest, that’s an area that the anaesthetist is appropriately trained and expert in managing. The surgeon will look to the anaesthetist for direction on what to do next.

When I was a young trainee, I had a patient with a very nasty traumatic injury to the eye. The eye needed to be enucleated – that is, removed – because it had exploded from trauma. Pulling on the eye during the surgery can cause the heart rate to slow precipitously and even stop, which was what happened. It was the middle of the night, when not a lot of people were around, I did what I needed to do with the anaesthetic machine, gave appropriate drugs and then started CPR. We had a good outcome, and the gentlemen recovered well.

However, the feedback I received from my mentor – a very senior anaesthetist – was that I shouldn’t have been the one doing the CPR. I should have directed somebody else to do that. It was totally appropriate criticism because all medical staff are trained for CPR, and I needed to take a step back and direct them. Once I was on the chest I was very blinkered, and much more likely to be fixated on a smaller part of the problem rather than taking the big picture view.

DP: At IML, we believe that reflection is often ignored in leadership. Leaders make huge decisions that impact lots of people, and then they typically don’t reflect on them. But that doesn’t seem to be standard practice in hospitals?

DJ: It’s certainly something people are very cognisant of now. We’ve always had a focus on looking at why adverse events happen, and what we’ve done leading up to them. Then having a non-judgmental discussion about how it could be avoided in the future.

DP: How do you stop yourself feeling vulnerable in those situations because, essentially, your performance is being judged?

DJ: It’s a challenge. Anaesthetists have the potential to be self-critical. But there is a dominant culture among Australian anaesthetists of being a very social and supportive fraternity. So there’s always a lot of interaction and a supportive view.

DP: You mentioned your mentor earlier. There’s an interesting statistic that only 21 per cent of CEOs of ASX 200 companies have a mentor. Whereas it seems in your occupation and your brand of leadership, mentoring plays a fundamental part.

DJ: One of the challenges with the whole concept of mentorship is that sometimes we try to artificially force it on a situation. I suspect a true mentor is someone who finds you rather than you find him or her. That can be a challenge during medical training. You often spend only short periods in any one hospital or department, maybe six to 12 months at most, so it can be difficult to find a true mentor. However, most large departments encourage the development of mentor/mentee relationships to guide you through growth in non-clinical areas like leadership and decision making – things that are often forgotten in the midst of other professional growth.

DP: One might expect that hospitals are full of accidental managers – people who, because of their technical skills, have ended up in management and leadership positions. What is the real situation in the medical profession?

DJ: One of the challenges hospitals face is that there are lots of bureaucratic and organisational problems, which have largely been solved in the business world. There is a greater effort now to train, particularly medical staff, in both leadership and managerial roles so that they’re much less accidental and organic.

DP: You decided to complete an MBA, and develop your skills in management and leadership. Why did you do that?

DJ: When you reach mid-level seniority as a medical specialist, you often find yourself on various hospital committees, and making accidental managerial or leadership contributions in different areas. It’s very easy to be resistant to ‘management speak’. But I could see there was some real theory behind it, and I was doing myself, the hospital and my patients a disservice if I wasn’t open to learning more about that.

DP: So, you went off to do an MBA at Deakin University, which is one of our accredited MBAs at IML. What did you learn?

DJ: The Deakin MBA was very satisfying. It confirmed some of the things I suspected – that the organisational challenges, business challenges, finance and human resource challenges that impact day-to-day hospital life are far from unique. We have a responsibility to properly understand

these so that we can improve the way hospitals work.

DP: What are some of the stand-out things that you’ve taken from your MBA?

DJ: Among the three things I’ve found most immediately relevant, Business Process Management taught me to look at the flow of information, staff, patients and associates, and how we create value. It blew my mind how complex all the processes are that our staff are undertaking on a daily basis. That means there are lots of areas for improvement and efficiency improvement.

The second area I thought was very interesting was Organisational Management and Human Resources. After completing the unit, you see that there is a huge amount of theory, both from the psychological point of view and behavioural theory, and I found that really useful.

The third area I found useful was Change Management. It’s all well and good to identify where there are problems, and then say, ‘Well, these are the solutions’, but implementing the solution is where everything falls down.

DP: So would you recommend professional development in management and leadership for specialist medical staff?

DJ: Definitely. The very nature of your specialist role means you have a position of leadership and you need to manage others. You might be lucky and do those well, but a lot of us don’t, and it’s our responsibility to learn to do them better.

In my line of work, where critical things are happening, you get the best performance out of your team when you’re calm and considerate in what you do. Internally, you may not be so calm, but projecting control and confidence is really important to have everyone else respond in a measured way in what could be a life-threatening event.

Leadership in 60 seconds

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or Snapchat?

Twitter.

Phone, email or face-to-face?

Email.

Name a leader that you admire and why?

Michelle and Barack Obama together, as a team, because of the integrity

they have in the way they approach things. Obama was always referred

to as ‘no drama Obama’. That sort of quiet, confident, competence,

I really admire.

Your personal view on leadership?

One of the important roles of leadership is being able to communicate to the team the destination, what we’re trying to do, and the reason why we’re trying to get there.

Which three guests would you invite to dinner to discuss leadership?

Steve Jobs is number one. Not because I see him as a great leader, but I think he’d be a great dinner guest. Another person would be Julia Gillard to discuss her experience as Labor leader. I find the gender issues in leadership in Australia really fascinating. Mahatma Gandhi would be my third guest, to provide a different historical context on leadership and where it is now.

Advice for somebody just starting out in any career?

Don’t be too worried about getting the direction and the decisions right for where you’re going. Focus a little more on decisions in a shorter horizon. You don’t know how your interests and skills are going to change.

What’s your personal resilience plan?

I really love running, trail running in particular, and also a bit of mountain biking – all of which are great here in Tassie.