The work landscape of the fourth industrial revolution, a term coined by Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum, looks very different to the one we grew up with in the 20th century. Industry 4.0 is characterised by universal connectivity, technological breakthroughs and fast-paced disruption that are facilitating a widespread shift to automation at the cost of traditional jobs.

We hear a lot about the jobs that we have lost, but what about the new jobs created thanks to advances in technology? Once children wanted to be firefighters and astronauts when they grew up. Now they want to be ethical hackers and drone pilots. Here is a selection from the growing list of jobs that didn’t exist five years ago.

11 jobs that didn’t exist five years ago

- Ethical Hackers help institutions identify the vulnerabilities in web applications and networks.

- Chief Growth Officers are also on the rise, along with growth hackers, typically social media or viral marketers or product managers, who focus on building the customer base by running rapid experiments.

- Chief Listening Officer oversees all customer communications, from social media to face-to-face.

- Chief Innovation Officer encompasses both product development and strategic direction responsibilities.

- User Interface/Experience Designers focus on making technology instinctive to use.

- Cloud services architects oversee a company’s cloud computing strategy.

- Cognitive computing architects make machines “think” like humans.

- Drone pilots, once the preserve of the military, they’re working in utilities, mining and insurance with roles in deliveries and wedding photography ramping up.

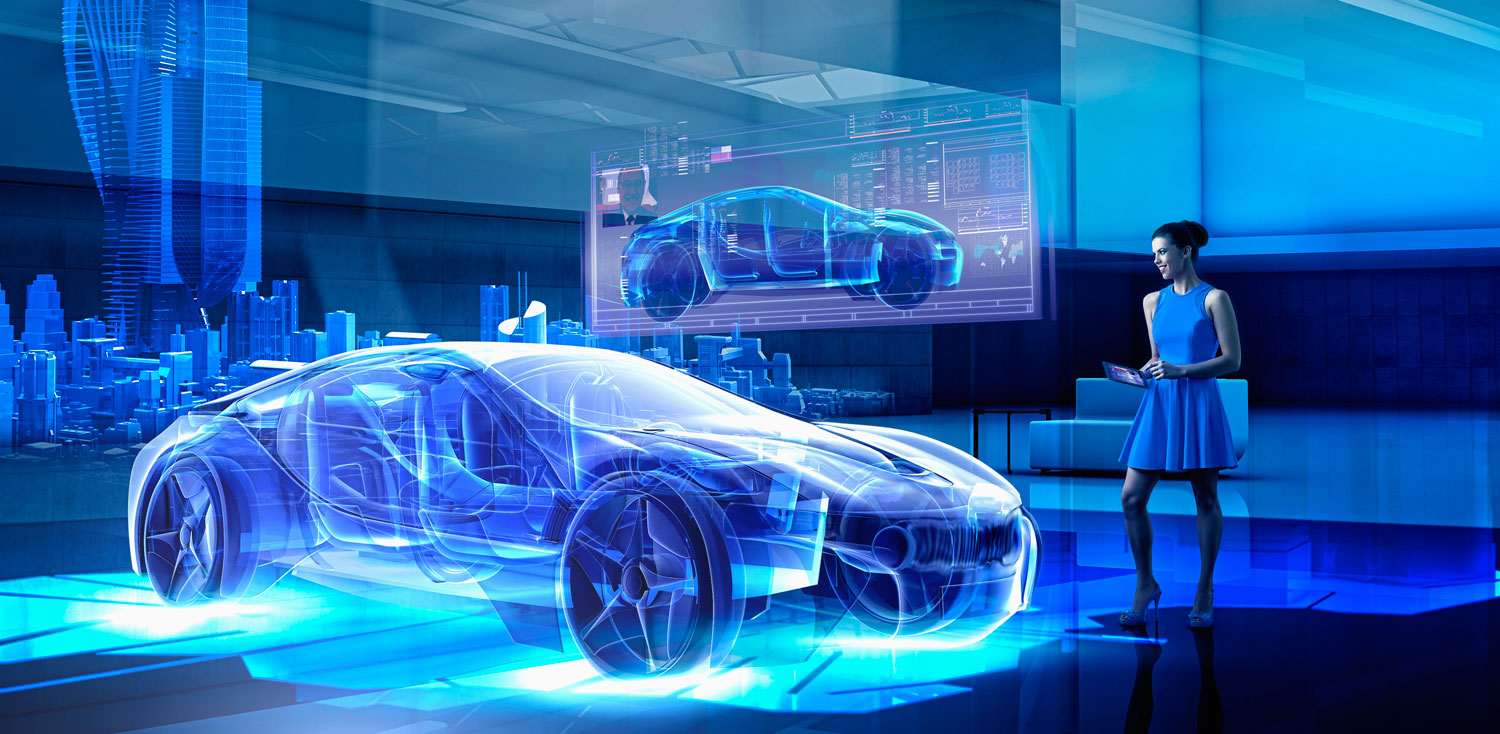

- Autonomous vehicle operators remotely operate driverless cars, collecting data for engineers.

- Digital prophet: a trend predictor. AOL has one.

- Jolly Good Fellow is the personal and spiritual development adviser at Google. Where else?