By Derek Parker

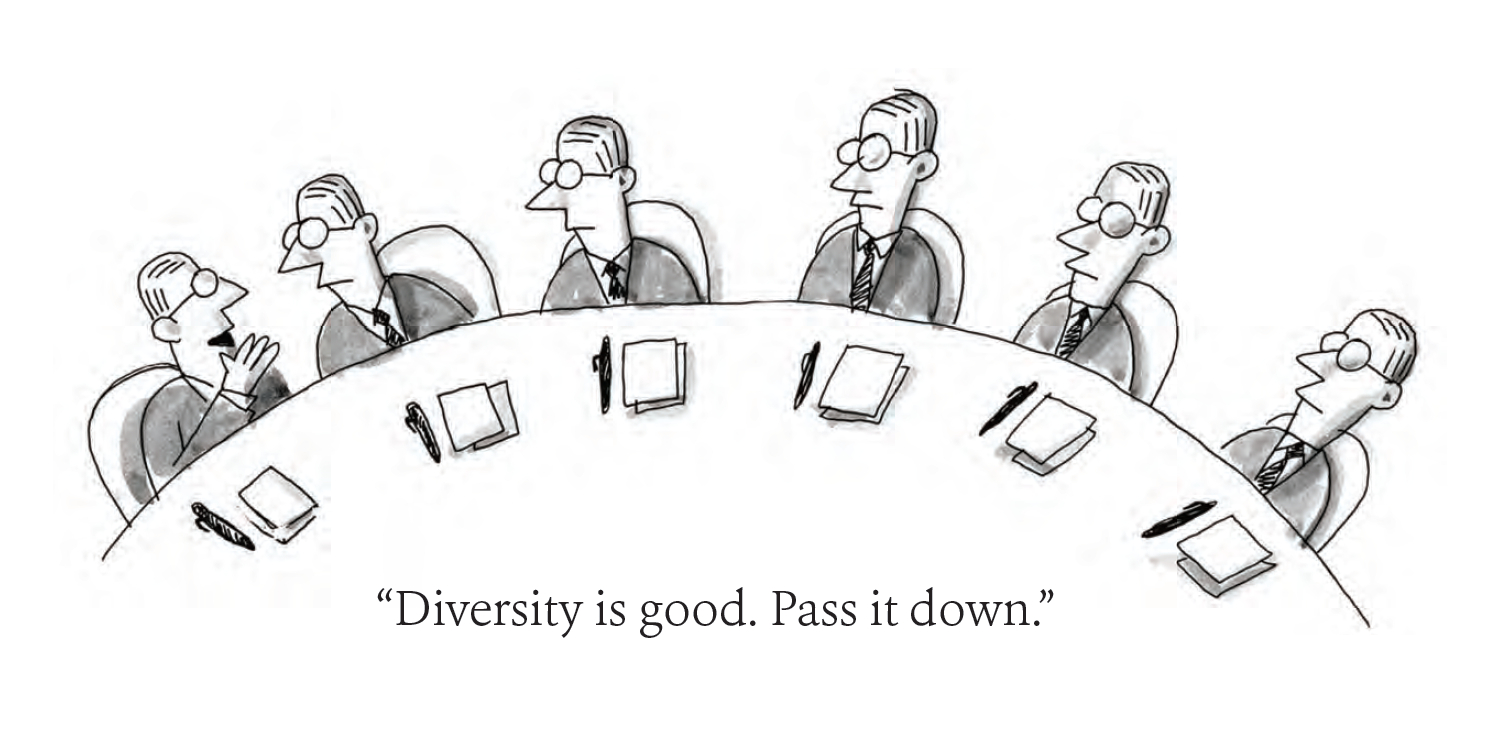

A sign on the door saying ‘business as usual’ can very easily turn into one saying ‘going out of business’ in today’s ever-shifting, hypercompetitive marketplace. The key to survival is new ideas, whether they relate to products, processes, organisation or technology. New ideas often come from new people, but many Australian organisations have not been successful at hiring new voices or, if they recruit them, effectively listening to them.

Everybody has some intrinsic unconscious bias and that can adversely influence hiring decisions, even when a company has a policy promoting diversity and inclusion. Yet there is a substantial body of research showing that diversity has a positive impact on the bottom line. Some of the most convincing is detailed in a 2017 report from McKinsey, Delivering Through Diversity, which indicated that gender diversity in management positions increases profitability, even more than previous studies had suggested. McKinsey’s data analysis showed that companies in the top 25th percentile for gender diversity on their executive teams were 21% more likely to experience above-average profits.

Likewise, according to the McKinsey data, companies with culturally and ethnically diverse executive teams were 33% more likely to see above-average profits. The pattern extended to board level, where companies that were more ethnically and culturally diverse were 43% more likely to see above-average profits – a significant correlation between diversity and performance.

These studies were in the US but specialists in the field believe that the Australian picture would be similar.

“It is very likely, since the countries are comparable, and it reflects my experiences,” says Theaanna Kiaos, an organisational anthropologist for Diversity First specialising in organisational culture, diversity and inclusion within Australian corporations. “What it means is that decisions made with higher levels of cognitive diversity are likely to be better ones. Once, homogenous boards or leadership teams might have been well-suited to make decisions affecting the company’s future. But it is no longer the case. We now live in a more complex, increasingly diverse world.”

AFFINITY BIAS

Unconscious bias arises when a first impression leads a senior person to favour someone in a hiring or promotion decision without knowing all the candidates’ capabilities. This is affinity bias: a ‘first impression’ preference for someone who has the same ethnic, cultural and gender characteristics as you do.

“It has its roots in primitive, tribal times,” explains Clare Edwards FIML, Principal of BrainSmart Consulting. “Our brains developed to consider anyone different as foe before friend. This reaction is still active in our brains today, mostly unconsciously. The issue for us now is how we overcome that and prevent it from creating group-think and stagnation.”

“It has its roots in primitive, tribal times,” explains Clare Edwards FIML, Principal of BrainSmart Consulting. “Our brains developed to consider anyone different as foe before friend. This reaction is still active in our brains today, mostly unconsciously. The issue for us now is how we overcome that and prevent it from creating group-think and stagnation.”

At one level, unconscious bias can be countered by mechanical processes, especially in recruitment.

Edwards explains that removing gender, residential suburb and tertiary education markers from applications can go a long way to mitigating unconscious bias. Holding panel interviews where panel members are of a diverse background and from other areas of the business is also effective.

“In the recruitment space, apps like Textio that have a ‘watch list’ of gender-biased words and phrases to avoid can help ensure the language and vocabulary we use is inclusive, gender-neutral and not influencing candidates one way or another,” she adds.

“Bias can be very subtle. For example, an ad asking for someone to ‘manage’ a team attracts more male candidates, as opposed to ‘developing’ a team which attracts more female candidates.”

Once a shortlist of candidates is created and applicants are selected for further interviews, the criteria being used for selection should also be absolutely clear to the interviewers. The criteria should relate to the capability to do the job most effectively. It is not about whether a candidate went to the same university as the selector, or if the selector can imagine themselves having a beer after work with a candidate. ‘Cultural fit’, while an important aspect in any selection, should not be manipulated to reject people who show themselves the best at doing the job but come from a different background to the selector.

These methods can be useful at preventing non-affinity candidates being knocked out during search and selection. They are part of an answer but not in themselves sufficient to improve diversity in an organisation. The other, and larger part, of the solution is to focus on the attitudes of the people engaged in the more advanced parts of the selection process.

FINDING THE RIGHT LANGUAGE

Many organisations have tried to address issues of unconscious bias through training but the results have often been mixed.

“Of all the companies we know who have taken part in unconscious bias training, not one of them was able to tell us, with absolute confidence, that it has resulted in sustainable behavioural change,” says Kiaos. “When we ask if leaders have become more insightful through the application of the key learnings, often there is only an uncomfortable silence.”

In fact, when executives and team leaders are told to think about their biases it can sometimes lead to a defensive reaction because it does not fit with their version of themselves. Kiaos emphasises that an environment of safety and trust is imperative to challenge biases and norms related to diversity and inclusion in an organisation. There must also be a deeper understanding of how the training fits into an overall diversity and inclusion strategy.

One problem is that unconscious bias training is often couched in the language of social science research and psychological phenomena. This can be alienating to executives whose expertise is business. For training to be effective it has to focus on workplace situations and implications, and on the business benefits of diversity. In addition, there needs to be a path for further action, such as giving a specific commitment to overcome an aspect of bias.

If the executives in the training course feel that they are being unduly criticised for being who they are, they are likely to become dismissive of the whole concept. Trainers need to think carefully about the language they use and the specific situation involved. The wrong type of training will not just be unproductive but counterproductive.

Chris Burton, Executive Director of Team Management Systems, a consulting firm that specialises in teamwork improvements, sees feedback mechanisms as essential.

“You need to take time and invest in learning programs that create a link between the inner world of how we think and the operational realities of how we get work done together. We need to illustrate to people how important it is that we accept, validate and incorporate our different perspectives because when we do this well, we are collectively performing better,” he says.

“Ultimately, what is universal when addressing bias is that you need to make the unconscious conscious by providing leaders with reliable feedback about how they process their world and how they prefer to approach their work.”

CHANGE OF MINDSET

Training to help to overcome unconscious bias is most effective if coupled with process changes and set within a business framework. But there is also another aspect: a conscious attempt by leaders, whether at the organisational or team level, to change their own thinking.

One strategy for this is presented by author Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. He differentiates between what he calls ‘system 1’ thinking, which is automatic and habitual; and ‘system 2’ thinking, which is slower and more deliberate. Each has its value but ‘system 2’ thinking delivers more considered outcomes and provides a way to get away from the trap of first impressions through self-awareness and reflection. Edwards has had success with a ‘perspectives’ exercise which invites people to consider how their beliefs and opinions were formed. This can cover areas such as values from parents and elders, religious and cultural upbringing, socio-economic status, and the political beliefs of influencers.

One strategy for this is presented by author Daniel Kahneman in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. He differentiates between what he calls ‘system 1’ thinking, which is automatic and habitual; and ‘system 2’ thinking, which is slower and more deliberate. Each has its value but ‘system 2’ thinking delivers more considered outcomes and provides a way to get away from the trap of first impressions through self-awareness and reflection. Edwards has had success with a ‘perspectives’ exercise which invites people to consider how their beliefs and opinions were formed. This can cover areas such as values from parents and elders, religious and cultural upbringing, socio-economic status, and the political beliefs of influencers.

“It’s not often that people take time to reflect and challenge beliefs they may have ‘downloaded’ or adopted but no longer serve them well,” she says. “We also encourage people to interact more with people who are traditionally outside their ‘in-group’ to expand their awareness of difference. The more diverse a group we interact with, the greater our understanding and appreciation of difference and the greater the likelihood of reducing bias in oneself.”

An easy test to check for unconscious bias in a hiring decision is to ‘flip it’. A selector who is having reservations about a candidate who comes from a background of diversity might ask themselves: would they still have those reservations if the candidate had the same cultural, ethnic and gender background as the selector? Alternatively, would a preferred candidate still be preferred if they came from a background of diversity? Questions like this help to turn theory into practice, and to understand the real-world consequences of unconscious bias.

A LARGER PICTURE

Theaanna Kiaos believes that moves to overcome unconscious bias should be set within a large self-development picture.

She says, “You can teach people conceptualisations of biases but it isn’t very useful until people connect with insight and personal feelings associated with biases in their own life. Overcoming biases comes about through identifying how these biases play out.

“Ongoing mindfulness training is also valuable. The mindful state allows one to observe their behaviour more easily, so it makes an effective combination with unconscious bias training. If an organisation can afford to do both, then do both.

“A critical thing is to avoid judging oneself negatively when an insight has become conscious. Rather, accept the cognitive deficit for what it is and carefully look at its impact in everyday life, then correct it by stopping that pattern of behaviour. Write it down, become familiar with it, and then stop it.”

Chris Burton offers another path. “Some of the most important resources used to eliminate unconscious bias are psychometric feedback tools used to generate focused self-assessment and self-reflection. A critical reference point for any leader is an awareness of their own default approach to decision-making, so they can then consider whether corrective action is needed,” he notes. “More broadly, as organisations embrace the importance of both learning and employee experience, these two factors have a multiplier effect to enable the workforce to navigate a successful path to better performance.”

A final step in dealing with unconscious bias is to look at personal changes of mindset in connection with the culture of the organisation.

“It would help, from a strategic perspective, to move diversity and inclusion policy and practice out of the jurisdiction of HR and put it into corporate strategy,” advises Clare Edwards. “There, it can function as a key performance indicator for strategic growth and organisational health. And that sort of shift would underline the importance of overcoming bias in order to help the company thrive.”

READ MORE ONLINE

Clare Edwards FIML, Principal of BrainSmart Consulting, shares extensive insights about tackling unconscious bias in recruitment. Read more here.

Theaanna Kiaos also goes into further detail in this article.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 print edition of Leadership Matters, IML ANZ’s exclusive Member’s magazine. For editorial suggestions and enquiries, please contact karyl.estrella@managersandleaders.com.au.