By Dr Tim Dean

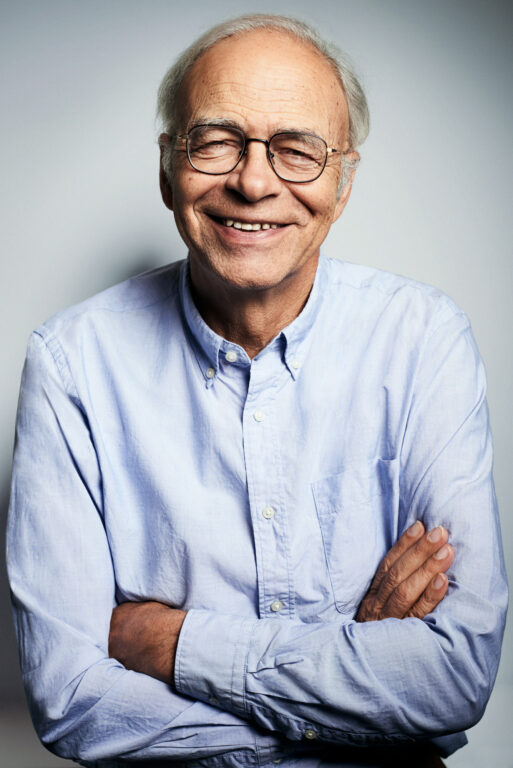

Peter Singer is a philosopher on a mission. The Australian-born bioethicist, who splits his time between the University of Melbourne and Princeton in the US, has spent his career advocating for genuine change to bring about his visions of a better world. This would be a world with less poverty, less animal cruelty, less suffering and one that enables creatures like us to flourish. And when it comes to his ethical views, he practices what he preaches.

Even before the release of his 1975 book Animal Liberation, which challenged the assumption that our species was the only one that had moral relevance, he had entirely stopped eating meat and using animal products, such as dairy and leather. And since the publication of his 2009 book The Life You Can Save, which argued that it is our ethical obligation to combat extreme poverty around the globe, he has donated more than a quarter of his income to charity.

His works have made him one of the most influential philosophers of the past half-century. Animal Liberation kicked off the modern animal rights movement and is still cited today by those who oppose intensive farming, animal testing and who promote vegetarianism and veganism. And The Life You Can Save led to a significant increase in charitable giving to alleviate global poverty, particularly by wealthy donors like Bill and Melinda Gates, and Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna, who co-founded the philanthropic foundation Good Ventures.

But in his view, it’s not just billionaires who can – and should – make a difference. Singer firmly believes that each individual ought to make a contribution to battling extreme poverty. “In the end, if everybody in the middle class and above in an affluent country were to give even a small percentage of their income, that would add up to a much larger sum than the billionaires could give,” he says.

And he believes that every life that is improved makes a difference. “When you talk about global poverty, some people say, ‘it’s such a vast problem, what can I do about it?’,” he says. “But when you look at concrete individuals who’ve been helped, it makes more sense to say, ‘look, even if I can’t eliminate global poverty – even Bill and Melinda Gates cannot eliminate global poverty – nevertheless, I can enable particular people to have better lives.’ And that’s really what matters.”

He also argues that our responsibility to help others in need is not limited to what we can do as individuals. We can multiply our impact by influencing those around us by becoming ethical leaders and running ethical organisations.

Leading an ethical organisation

What does an ethical organisation look like? All organisations, whether for-profit or not-for-profit, are required to obey the law and to pay their taxes. But Singer says that being a truly ethical organisation goes beyond this. “For organisations in affluent societies, where people have the capacity, it’s really important to make a positive difference to the world, and this often goes beyond their legal liabilities and their code of ethics as well.”

A genuinely ethical organisation would abide by two broad ethical principles: the first is to “do no harm” to individuals and society at large; the second is to work to do good in the world.

Indeed, Singer believes that if leaders took the “do no harm” principle seriously, it could have a profound impact on the way they operate, such as by obliging them to reduce their carbon emissions. “In an interconnected world, where we now know that our greenhouse gas emissions do cause harm, ‘do no harm’ is much more far-reaching than people thought it was,” he says. “It means that we’re responsible for the harm caused by our greenhouse gas emissions. And we’ve seen recently in Australia, that that can be very substantial, and it’s even worse in countries where people don’t have the resources to deal with similar problems in the way that we do. So if organisations take ‘do no harm’ seriously, reducing emissions is a necessary ethical step.”

For some businesses, that might also mean fundamentally changing the products or services they provide, particularly if they’re known to be harmful. “Given the knowledge we have about tobacco and cancer, I think the entire cigarette industry is an unethical practice,” he says. “It’s very difficult to stop that, of course, because if one company stops and another sees a market opportunity where it’s legal, it will still happen. But I still don’t think that’s a business that people should be in.”

An ethical organisation should also ensure that it is working to make a positive impact in the world, whether it’s for-profit or not-for-profit. That often means being mindful of where the organisation can help those who are less fortunate. “We have an ethical responsibility to reach out and help people who are much worse off than we are through no fault of their own, just through the situation in which they were born or grew up.”

For business leaders, this means thinking beyond the current quarter’s results or their responsibilities to shareholders, and to consider the wider impact. “In the last few decades we have moved away from Milton Friedman’s view that a company’s only responsibility is to return dividends

to its shareholders – within the law, of course – and no more than that. I think we now recognise that they do have wider responsibilities to a variety of stakeholders, to their supply chain, consumers and the broader communities in which they operate.”

In addition to this being an ethical responsibility, Singer points out it can also be good for business, such as by attracting highly motivated ethical staff. “It can actually be a highly successful strategy in terms of enhancing the reputation of the business,” he says. “It can motivate workers in a different way from simply paying them good wages and bonuses. When workers know that they’re working for an ethical company that donates a proportion of its profits, it might encourage individual employees to donate themselves, by matching their donations. This gives workers a better sense of the point of what they’re doing.”

Acting ethically can also protect against reputational damage, which as we’ve seen from recent banking scandals, can be highly costly. “In the for-profit sector, leaders need to be thinking about things like reputational damage, at least in part because they’re going to have to explain to shareholders why they’re doing things that might reduce profitability,” says Singer. This extends to not-for-profits too. “For non-profits, there are things that might have an adverse impact on donations,” he says. One example is the scandal that rocked Oxfam in 2018 after it was revealed that the charity had covered up an earlier investigation into its staff hiring sex workers in Haiti, where prostitution is illegal. The backlash from this cost the charity millions of dollars, which in turn hampered its ability to deliver essential services to people in need.

Leaders need moral courage

Many leaders might believe that a code of ethics is enough to ensure they are working to a high ethical standard. However, Singer points out there’s more to ethical leadership than adhering to a code of ethics. “The problem with some codes of ethics is that they become a tick-the-box kind of exercise,” he says. “And that can become a kind of a routine, in which there isn’t much ethical thought about what it means to tick this box. I might just be complying with the letter of the code when, in fact, the spirit of the code is not being met. People do need to be thinking ethically beyond the code, and about the purpose of the code, and about what might be missing, or whether the code is not really being properly applied.”

Genuinely ethical leaders shouldn’t rely on a code of ethics to solve all their problems, and should be thinking ahead and anticipating ethical issues before they arise. This often means going against the grain or challenging the status quo. “Leaders have a responsibility not to just go along with how things have been done in the past, but to take a good look at what past practices should be challenged,” he says.

Sometimes this will mean an ethical leader will have to stand up for what they believe is right, even if it could cost them their job. “Clearly there are some situations in which you ought to be prepared to lose your job because you’re in a completely unethical industry,” says Singer. “I realise that’s asking a lot from people, especially people with families who are dependent on them, but sometimes I think there is no other ethical way forward. And in the end, it may work out best for the employee too.”

Singer’s advice for an ethical leader is to continually remind yourself of the bigger picture. “Look at all of the consequences of your decisions. Don’t just look at the consequences for yourself. Don’t just look at consequences for your shareholders, or even for your staff. Try to be universal in your scope,

try to look at the consequences for everyone.”

It might seem that Singer is setting a high bar – and he is. But even if you don’t subscribe to his particular interpretation of ethics (see boxout), he reminds us that we each have a responsibility to act in accordance to our moral values, and this often goes beyond the requirements of the law. This is especially important for leaders, as they serve as exemplars for those around them. If a leader lapses in their ethical standards, this can give leave for others to do likewise. But conversely, if they act with integrity, they can magnify their effect on the world by influencing others to act ethically. That’s true ethical leadership.

Dr Tim Dean is a Sydney-based philosopher and writer.