By Derek Parker

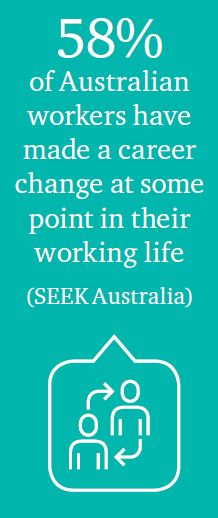

Work takes up a major part of our lives, but a surprising number of us are dissatisfied with what we do to earn our daily bread. Fifty-seven per cent of Australian workers feel ‘stuck’ in their jobs and a similar number are considering a major change of career, according to independent survey data commissioned by placement firm SEEK. “According to our data, 58% of Australian workers have made a career change at some point in their working life. It happens at every stage but there are some differences between generations,” says Sarah Macartney, Head of Corporate Affairs at SEEK. “Three-quarters of people aged 55-64 are more likely to have made a career change at some point in their working life than people aged 18-54, which is a bit over half.”

She notes that the reasons for making a change vary but some of the most common motivators include a better work-life balance (18%), desire for a new challenge (11%), pursuing a passion (10%), and wanting something more fulfilling (7%). The last one is a more popular reason within the 35-64 age bracket (10%) than 18-24 year olds (2%).

Staying in a job that you don’t like can be a source of stress, worry, and eventual burn-out. But even as career changes for senior people become more common, no-one says it is easy. Making a successful transition requires planning, preparation, and support. In short, you have to know what you are in for.

Changing your identity

A dose of self-assessment is a necessary place to begin. Establish exactly why you are dissatisfied and what sort of work might be better. This can involve talking to mentors, advisers, and, if possible, people who have made successful transitions.

Linda Jeffrey, a career consultant and professional member of the Career Development Association of Australia, notes that personal identity is often closely linked with one’s job, so making a change can raise significant psychological issues, particularly when change is not through choice.

“It is important that this stress is acknowledged and that individuals have access to effective support,” she says. “There can be a sense of loss of control of your life at a time when you have previously felt successful and quite confident in your future.

“There can also be concern that being middle-aged or older will be a barrier to finding a new role or direction. This may sometimes be the case, but there are also barriers for younger people, based on their limited experience. So, you should focus on what you have to offer rather than how old you are.”

She believes that creating a good CV is a fundamental preparation for change. In fact, it’s as valuable to the individual as it is to a prospective employer. The drafting process gives the individual an objective view of what they have to offer in terms of transferable skills, strengths and experience, and highlights areas where they need to upskill.

Knowing your strengths and weaknesses is particularly important for C-suite leaders who are considering taking up a board position or a consulting role. Hands on management is very different to strategic policymaking and executive oversight.

Self-assessment was crucial to Tamsin Garrod, who moved from a role as a medical researcher in a laboratory to a healthcare management position.

“I have huge respect for researchers but it became clear to me that my passions, skillset and personality did not align with the job. I am driven by working with people and I feel energised when I interact with others,” she says.

“Once I had defined my ideal role, I identified areas where I required development to succeed in a career transition. For me, it was increasing my understanding of business processes and governance, and further developing my knowledge of people management. I upskilled by completing an MBA, which really helped underpin my progression. Professional development is key in a successful transition.

“I also set a specific end date for my previous role and informed my manager of my decision to change career. I spoke to a number of people who had experienced similar changes, and they confirmed that making the leap is much harder while remaining in your current role. It can reduce your level of motivation and commitment in seeking the new role.”

Do your research

Once the decision to move has been made, develop a list of options for change. Speaking to someone who is already working in the area that you would like to move into can help in understanding exactly what the job entails, including the amount of paperwork and the prospects of advancement.

If you are moving into a completely new area of work, find out what sort of training and reskilling might be needed. If it means going back to university or a college course, be prepared to be in class with younger people.

In most cases, a career change means a drop in income, at least temporarily. This means that a thorough review of your financial situation is necessary, as well as discussions with family members and others who might be affected. A crucial question is: is the reduced income something that can be compensated by improved work satisfaction or work-life balance?

Macartney acknowledges that financial issues inhibit many people from making a career change. But she advises that there are proactive things that can be done, such as drawing up a budget, cutting back on spending, and using annual leave while looking for suitable jobs in the industry, sector or company you want to work for.

Any change involves risk, and that has to be weighed against the stability of a regular salary. A reduction in income can itself be stressful, so make sure that the overall equation adds up. In other words, know that you are not trading one type of stress for another.

Flying solo

The option of leaving corporate life to set up or participate in a small business or a start-up is an idea that many leaders find appealing. But Alan Manly FIML, who left an IT role to take up a partnership in a tech start-up, warns that it requires careful consideration.

“If you want to follow the entrepreneurial route, dream up an idea and do a business plan,” he says. “That brings the dream back to practicality. And then when every detail is covered, double the time to be profitable, double the investment required, and allow twice the work and hours needed. That is a good start.”

After being successful with the startup, Manly then made another career change, when he took up a position as a partner in a private computer programming college.

“In my case, my previous skills were transferable. I was experienced in a service industry after years in the computer industry working in post-sales marketing. Education is a service industry, so it was very similar. I had already taken a wage drop when joining the startup, so taking on the computer college role was another step in that journey.”

Another issue to consider, if you decide to operate as a sole-person business, is social isolation. Many people in corporate roles become used to having people around them, and are familiar with the social life that is a part of many workplaces. Working by yourself means that that aspect of community, and the company of colleagues, no longer exists. So before taking the one-person-band route, ensure that there is an alternative network of personal support. It might be family, friends, or peers in similar circumstances, but there needs to be a sense of ongoing connection.

Employer perspective

It is important to know that making a career change does not prevent you from being hired, according to Macartney.

“If anything, the majority of employers look favourably upon those making a switch because they believe these individuals will be more motivated to learn and are more likely to succeed in their new role,” she notes. “Our survey asked people on the hiring side if they would consider hiring someone who had recently changed careers. More than four in five said they would.”

Tamsin Garrod advises that, when applying for a new job, candour is the best option. Highlighting the positive lessons from your previous role but also clearly stating the reasons for the change reassures a potential employer that you are committed to making the transition. Pointing to any skills that are transferable is an aspect that is also likely to persuade prospective employers.

Macartney agrees, emphasising the need for a solid plan. “Talk to a careers professional, keep your expectations realistic, consider all your options, and think holistically,” she says. “Then, when you’re ready, just do it.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 print edition of Leadership Matters, IML ANZ’s exclusive Member’s magazine. For editorial suggestions and enquiries, please contact karyl.estrella@managersandleaders.com.au.