By Karyl Estrella MIML

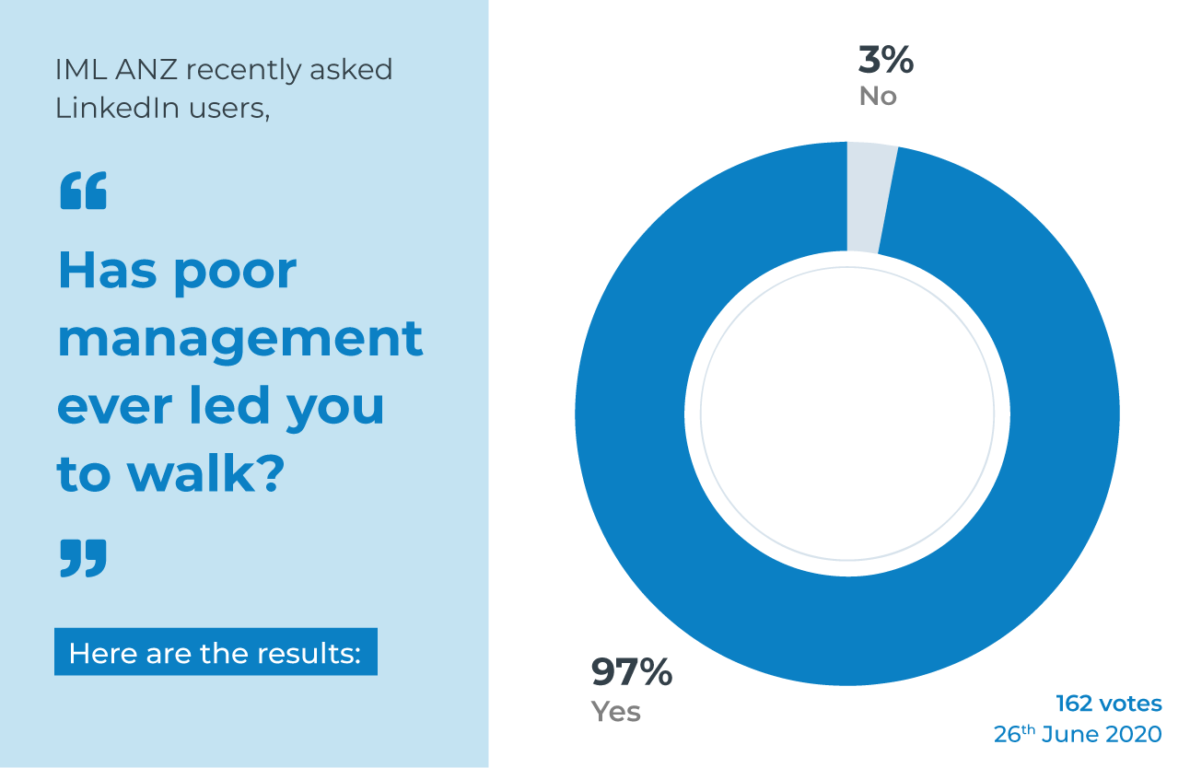

Bad management is bad for business. We’ve all heard the adage, ‘people leave bosses, not jobs (or companies)’. To test out that statement, we ran a quick poll on LinkedIn and unsurprisingly, 97% of respondents confirmed that a bad boss has caused them to walk. What’s more, over the last ten years, the National Salary Survey found that an average of 28% of employees leave because of problems with their manager. When you consider that it costs an average of $20,493 to recruit, hire and train a new employee, then poor management practice is just not something you want – both as a leader and for your organisation.

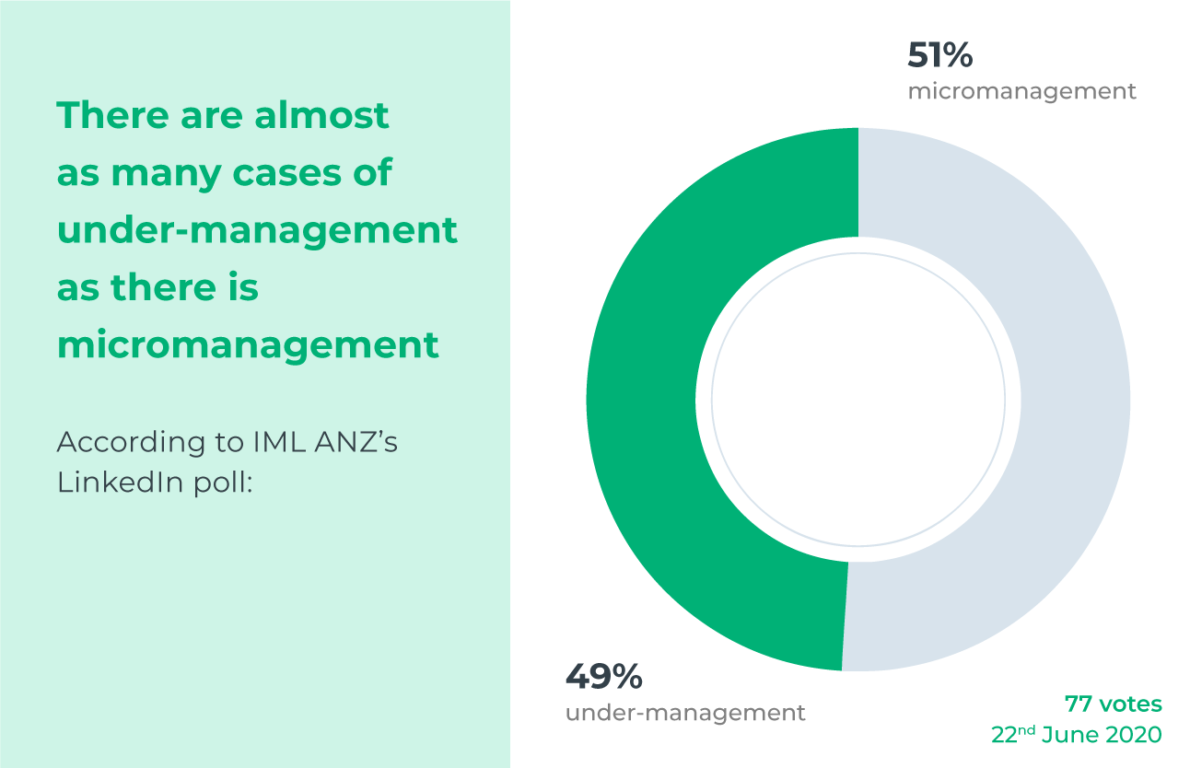

Often when we picture a terrible manager, we see a micromanager. However, on the other end of the spectrum sits another dangerous practice: under-management. A term coined by author and management trainer, Victor Lipman, under-management may not be as well-known as micromanagement, but its effects are equally damaging. In fact, in another recent LinkedIn poll we conducted, almost as many people report experiencing under-management as they do micromanagement.

How does over- and under-management happen?

According to executive coach and leadership programs facilitator, Rob Brennan, the tendency to under-manage might be influenced by an individual’s career path. “An individual can sometimes drift into reduced competence in new areas required by the organisation,” Brennan explains.

“Under-management can arise through the career journey of a person who initially becomes a trusted employee but who starts to disappear into the woodwork and then gradually slips into being a less productive and less innovative person.”

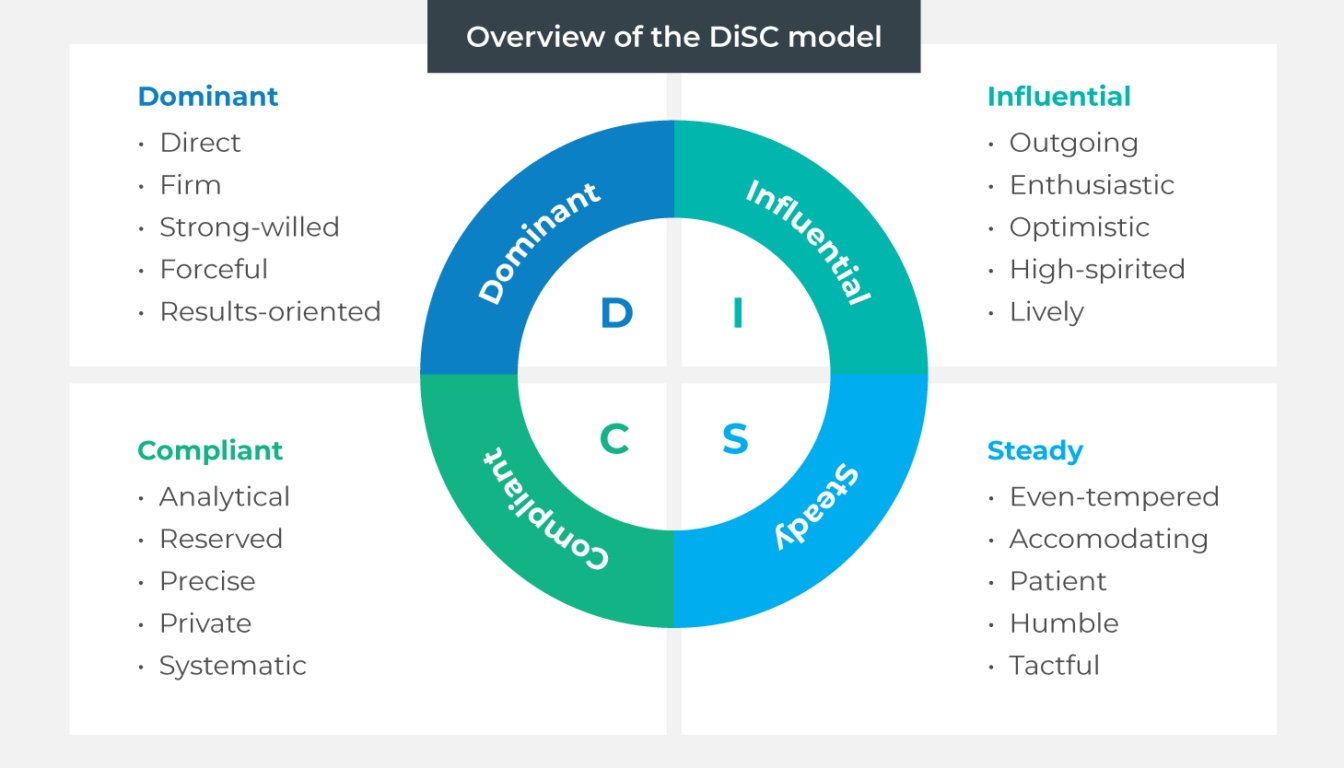

Brennan also believes that a manager’s personality plays a role in their tendency to either under- or over-manage. “Micromanagement is often displayed by those with personalities who value details,” he says.

Using the DiSC profiling tool for reference, Brennan points out that the ‘D’ and ‘C’ personalities are most likely to display micromanaging behaviour. Both profiles are characterised by a strong need for control, which may feed the desire to know every detail and a reluctance to delegate. Meanwhile, those who under-manage could most likely fall under the ‘I’ and ‘S’ profiles. In these profiles, there is a tendency for indecisiveness due to a fear of disrupting harmony or offending others. So, a manager might sacrifice providing proper guidance just to be liked.

Why it’s essential to get the balance right

The dangers of veering towards either end of the management spectrum impacts both the manager and the team member. For the manager, the lack of motivation to achieve more could result in their becoming what Brennan calls a “quit-and-stay person.” That is someone who no longer adds value to the organisation and has become complacent, believing the trust that they receive is a signal to exert less effort in their work.

On the other hand, a team member who sees an under-manager may start to question how the company decides what makes anyone’s work valuable. “You could have someone who sees a manager get paid more to do nothing, that can be demotivating,” Brennan adds. When this occurs morale drops, and so does productivity.

The goal, therefore, is to strike a balance. Brennan believes that bosses achieve balance when they go beyond a ‘management’ mindset and into a ‘leadership’ focus. “Empowering your team, inspiring them to improve and being clear about the expectations set for their role is what it means to be a leader,” he adds.

Brennan also emphasises that leaders possess a specific set of skills that allow them to maintain that balance. Those skills include emotional intelligence, coaching, and setting strategy, to name a few.

Apart from developing leadership skills, there are also some steps that organisations, managers and their team members can take to combat under- and over-management.

- Organisations need a clear focus. Right from recruitment, a company must have clear and specific expectations of what they need their managers to achieve for the business. Setting targets and goals must also go hand in glove with accountability. Managers who are held accountable for their teams will likely do their best to ensure they are supportive but also display trust.

- Managers must know their teams. According to Brennan, avoiding over- or under-management comes down to the quality of a manager’s relationship with their team members. He suggests regular (not just once a year during the performance review!) and open communication. And because every person is different, it’s best to find out what each team member’s preferred management style is. What this allows a manager to do is to determine what Brennan calls the ‘tender-tough’ leadership approach for each team member. He explains that ‘tender’ involves displaying support, encouragement and listening while ‘tough’ includes the ability to direct, to assert themselves and to handle conflict. ‘Tender-tough’ leadership requires finding the middle ground that works for each team member.

- Individuals should provide feedback. Building rapport with your manager is an excellent way to ensure that you can freely give them feedback. Be thoughtful and tactful of course. Remember, the best working relationships are based on genuine care and concern for each other.

Become a better manager by striking the balance. Instead of taking full control, display trust and provide clear guidance. Instead of totally stepping back, communicate regularly and listen intently. Remember, the antidote to bad management is balanced leadership.